Mitchell, Brody, Shannon, and Shelby,

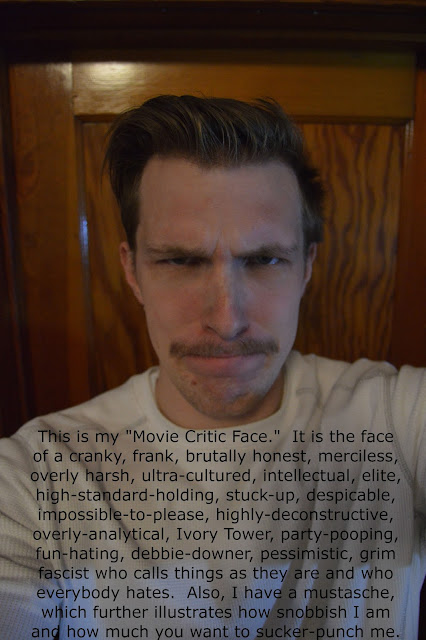

Like most Christian movies, The Shack wasn't the best. By no means was is bad, but it's something that definitely good have been better. It's every so slightly cheesy, although mercifully much less so than a Hallmark Channel original movie. I watch Oscar-winning films all of the time, so I know what quality storytelling and filmmaking looks like. I've seen films that evoke God which are truly great, and this isn't one of them. I'd imagine that, realistically, a man having a conversation with God would be mighty impactful and would take some incredibly impressive writing in order to convey, but you don't see that in The Shack. It does an acceptable job at doing what it's supposed to do, and many Christians going in will be pleased, but again, whenever I see a film like this that's merely okay, I think that its a wasted opportunity. Christians who have the Holy Spirit in them should not only be able to confess the Truth, but be able to confess it more Beautifully than non-believers are able to confess untruths. The Truth about God is powerful and moving, life-changing, but this is not one of the movies that has changed my life. Schindler's List changed my life. Dead Poet's Society changed my life. Those weren't necessarily Christian films, and yet they deeply spoke to me as a Christian. So why is it that Christian films, even when they reaffirm what I believe, don't really speak to me?

Like most Christian movies, The Shack wasn't the best. By no means was is bad, but it's something that definitely good have been better. It's every so slightly cheesy, although mercifully much less so than a Hallmark Channel original movie. I watch Oscar-winning films all of the time, so I know what quality storytelling and filmmaking looks like. I've seen films that evoke God which are truly great, and this isn't one of them. I'd imagine that, realistically, a man having a conversation with God would be mighty impactful and would take some incredibly impressive writing in order to convey, but you don't see that in The Shack. It does an acceptable job at doing what it's supposed to do, and many Christians going in will be pleased, but again, whenever I see a film like this that's merely okay, I think that its a wasted opportunity. Christians who have the Holy Spirit in them should not only be able to confess the Truth, but be able to confess it more Beautifully than non-believers are able to confess untruths. The Truth about God is powerful and moving, life-changing, but this is not one of the movies that has changed my life. Schindler's List changed my life. Dead Poet's Society changed my life. Those weren't necessarily Christian films, and yet they deeply spoke to me as a Christian. So why is it that Christian films, even when they reaffirm what I believe, don't really speak to me?

While my criticisms of the movie's shortcomings as a piece of art are plain and frank, that's not what I want to talk about here. That's more suited for an official review of the film. This is not a review of the The Shack, but rather, a review of some of the claims that people have made about it. To my surprise, it wasn't just movie critics who were criticizing The Shack, but people of faith. To quote some of the stronger language that I found, "You are accepting the doctrine of demons in place of the Word of God."

Let me be clear about this: I do not think that The Shack teaches any sort of heresy. The film is about a man named Mack whose daughter is murdered in the titular shack, after which his spiritual life dries up because he fundamentally doubts the goodness of God. He gets in invitation from God to come back to the shack, and arrives to find that it actually was God who invited him. He meets the whole Trinity there, and they spend a week talking about why God allows bad things to happen to good people. Some of the points that God makes are that Mack is seeing the world through the lens of his suffering, that he doesn't understand that God entered in to that suffering, that God grieves too when loved ones die, that He loves the murderer, too, that we are to forgive those who sin against us, that Original Sin infects us all, and that He's all about relationship, among some other things. The book went into a bit more detail on these subjects and discussed a wider variety of topics, but the movie is a little more focused and gives priority to discussing the subject matters pertaining to Mack's suffering. In all this, I agreed with everything that it said, which wasn't too hard to do, considering that the film didn't say anything particularly controversial. This was fairly standard Christianity.

It surprised me, then, when I discovered all of the distrust and accusations of heresy leveled against this film. The first thing that I heard was that the film preaches a message of Universalism, which is the belief that since God loves all of us, we're all going to Heaven no matter what. Nowhere in its runtime does The Shack preach this, or even suggest it. Yes, it says that God loves everyone and forgives everyone, but it did not say that all were saved. In fact, the book goes into a bit of detail about this. God says that He loves the man who murdered Mack's daughter, but He also says that not everyone who is forgiven chooses to accept forgiveness. The book actually mentioned it quite a bit that God is about relationship, and that while forgiveness makes a relationship possible, one must actually accept the relationship in order to be in it. That isn't a Universalist message. Granted, the movie doesn't find time for that particular bit of wisdom and thus isn't as explicit, but I still don't feel that at any point it suggested anything heretical.

God says that He is particularly fond of Mack. Mack asks "Is there anybody you're not particularly fond of?" God said "No." This might have also been construed as being Universalist by some, but I think it would actually be more heretical if God had said the opposite. If God is Love, and God created the entire world and everything and everyone in it, then God must be particularly fond of everyone. If He didn't like someone, then He would admit to having made a mistake, and furthermore, if He didn't like sinners, He wouldn't have died for us. A God who likes some righteous people and dislikes other, more sinful people who aren't in His Grace, reminds me of the false god of Islam, who selectively chooses people to forgive.

So far, still no heresy.

How about God being friendly and jovial? Yes, people have in fact found issue with that, so let's discuss it. Is it heretical for someone to have a conversation with God in which God isn't judging him, and isn't condemning him? Possibly. God is, after all, the final Judge, and one could say that The Shack trivializes that aspect of His personality by not evoking it much and instead focusing on His friendlier, gentler side. But the Bible says that He will reserve that for a later day, which will become the Day of Judgment. Yes, God desired holiness in your life, and God condemns wicked actions and foolishness, but He doesn't get us to the point where He wants us to be by coercing us. He gets us to that point by having a relationship with us, and through that relationship transforming our desires, which is what the film depicts. He takes sin very seriously, it's true, but He takes the enjoyment of our relationship with Him even more seriously. The most dangerous sins are those that distort our faith and prevent us from being close with Him, and it was such a sin that God lovingly extracted from Mack in the story. Mack doubted God's goodness, and believed that he would make a better judge than God. God didn't get demanding with Mack and didn't see him in terms of His sin, as a walking record of rights and wrongs, as a problem in need of judging and fixing. He saw him as a child who had gone astray and needed extra attention and a taste of the joy that waited for him in Heaven. Was He angry? Not particularly, but God also mentioned that even though He loved everyone unconditionally, even though He was especially fond of everyone He had created, He still got angry sometimes. That's scriptural, and it also works against the accusations people have made against the film that it's Universalist and that it depicts a hippie God who has no standards. God does have standards; He just doesn't enforce those standards in ways that we find intuitively obvious. Some people are under the impression that this movie has a false New Age god, but it's actually quite old-fashioned.

All these, so far, seem like really sloppy criticisms waged by people who haven't even watched the film, or weren't paying attention too much. There was, however, one aspect of God that everyone noticed that you didn't have to look to hard to see. I'm also utterly shocked that this is being considered heretical.

So let's get down to it.

First starting with the not-so-controversial: Jesus is depicted as a Middle-Eastern carpenter. I think we can all agree with that.

A little more controversial now...not really, not in my mind, but apparently in the mind of enough people:

God the Father takes on the form of a black woman. God the Holy Spirit takes on the form of an Asian woman. Some people, including my sister (your cousin) have said "I've read the Bible and nowhere in it does it say that God can take any form that He pleases. God is a man and would never present Himself as a woman!" Those are interesting points, and I understand where they come from. I, too, believe that we should understand God's character in terms of how He's revealed ourselves to us. God is not all things. He is not a God without a distinct personality. He is not a featureless concept without peculiarities, as Plato imagined Him. He isn't bland and predictable. He isn't inoffensive. He chose to be a certain way and we are to accept the manner in which He decides to identify Himself. We like to think of God as being beyond names, beyond human language, but in fact He chose to give Himself a name in a human language, Yehweh. God chooses to express Himself and His Love in ways that seem arbitrary. He isn't a deistic God, but a personal God, who acts as a person and has the distinctness of a person, so we as Christians must believe in Him as He has chosen to be. In scripture, He primarily identifies as a Father, and we are to take that very seriously.

But at the same time, the Bible also says that we are "born" in God. He gives "birth" to us. He is described sometimes as a womb, and as a breast. In Isaiah, it says that "As a mother comforts her child, so I will comfort you." Clearly, he has motherly characteristics. And also, although the bible doesn't say that God can take whatever form He pleases, it never says that He can't. Seriously, this is the all-powerful God, Creator of Heaven and Earth. All of the diversity of the human race can be found in Him. Both man and woman are created in His image. Are people actually telling me that he can't appear as a black woman?

"Oh, but God would never compromise on his modus operandi! He's described himself as being like a mother, but never actually as a mother! He's always done things a certain way and he would never compromise on that for the sake of one person!"

Yes, but there was no precedent for Jesus, either. There was no precedent for Pentecost before it happened. There wasn't precedent for God appearing as a flaming bush, either, nor has there been any incident of Him doing so since then. Sometimes, God does something new. I can see Him appearing as two woman and a man for the sake of one man. In the book, as well as the movie, He said that He needed to shatter Mack's preconceived notions of God, that God was some bearded white man stoically executing judgment from afar, and that Mack would understand God better if He appeared to him as a woman. God also acknowledged that Mack had a terrible father, and wasn't ready to understand God as a fatherly presence yet. When Mack is finally ready, God comes to him as father.

"But God wouldn't compromise! He never meets someone halfway! He demands that you accept Him the way He is without first feeding you an adulterated version of the Truth!" Okay, that's an interesting argument, and in some ways it's true. God uses half-truths to His glory when people spread them, and uses evil when it occurs to work for His will, but God Himself doesn't tell us half of the Gospel whenever He directly speaks to us. He always speaks the unadulterated Truth. And as it happens, I thought that He spoke the unadulterated Truth in The Shack, or at least as much as the author could comprehend it. It is true that God has described Himself as feminine and motherly. It is true, as far as I can tell, that God can present Himself as a Mother if He so chose. Perhaps it's controversial for the author to suppose any choice of God, since we don't know if He has chosen or ever will choose to appear to someone as a woman, but isn't supposing that He would never do that also a supposition of His character? In any case, this is fiction, and the author isn't describing an actual encounter with God so much as a hypothetical one, and he's also trying to illustrate God in ways that will help people make connections that they might not have easily come to before. I'm sure God is using this depiction of Him to His glory, even if He never has and never will present Himself in the exact same way as in the film.

The final criticism took me by surprise. People said that the film promotes idolatry. What's that? Idolatry? That's was a pretty serious accusation, and I kept it in mind before going on to the theatre. Perhaps there was a humanistic moral in the story teaching that family is just as important as God. Perhaps there was a mention of how good the creation is and how we are to love creation. Something like that, something that would suggest that there are things that we are to put on equal footing with God. There were no such themes. Later, when I looked at these charges of idolatry in more depth, I saw that the issue that people had was that the film should depict God in any way, shape, or form. You know how Islam prohibits anyone from from making any physical representation of a prophet, or depicting God in any form of art? That was pretty much the outlook of these critics. I saw a lot of people quoting of Exodus 20:4, "You shall not make for yourself an image in the form of anything in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the waters below." To my ears, this is a very primitive and one-dimensional argument that doesn't appreciate the complexity and the purpose behind that command. Most of us learn to understand the actual meaning of this command early on, and I wasn't expecting fully grown adults to have such a simplistic view on it. They seemed very concerned with following the letter of the law but not necessarily the spirit of the law.

Allow me to explain idolatry. Idolatry is, first and foremost, valuing anything more than God. God must be the source of all value and the central focus of our lives, our reason for living. That's how most adults understand idolatry today, and just about any church that I go to will make a point of mentioning that it's even possible to idolize our spouses and children. We can idolize other things. Some of us put our ultimate self-worth in our jobs, and that's idolatry. I see many humanistic people idolize the arts; just listen to Viola Davis's acceptance speech at the Oscars, or what Meryl Streep said at the Golden Globes. When you tune into those award ceremonies, you're basically watching a bunch of wealthy people congratulating themselves on the art that they created, and defining themselves by their artistic achievements. It's completely disconnected from the real world that matters.

This is where I have to confess something, actually. I worship art. Specifically, good art. Truly, I do. I am idolatrous. As an artist, I am particularly vulnerable to this, because I see art in a different way than others. I become proud and attached to my own art when I've completed it. I adore it. What can I say? I put hard work into it, so it's hard not to value it! When I see good art, I tend to take it very seriously, more seriously than I should. Perhaps I even become jealous of the artist who created it, because I wish I could have accomplished what they have accomplished. I'm jealous of Steven Spielberg, because he gets to make films with John Williams scores. I'm jealous of George Lucas and J.R.R. Tolkien, because they created the two greatest works of fantasy in modern art that I'm always afraid that I will never live up to. Because I idolize these images, I break another commandment, because I begin coveting my neighbor's wife.

Furthermore, I want to write my books series. I put my self-worth in self-expression. This self-expression in many ways makes me vulnerable, which is a virtue, but I begin idolizing that virtue instead of putting my faith in God's love for me. I begin making the meaning of my life all about how perfect I can make my art, but that's not why I was created. I was created to be loved. Idolatry distracts me from that.

That is the most dangerous kind of idolatry, and that is the evil spirit that Exodus 20:4 ultimately wishes to protect us from. Boiling it down to this ridiculous formula of "All art depicting sacred things is bad" is oversimplifying the command, and missing the point. God commanded the Jews to make many beautiful things, including statues of cherubim. The trick here was that God didn't want the Jews to worship the art itself, but what it represented. We humans are visual creatures, and often do need physical prompts to remind us of the things that we value. When I went to a Greek Orthodox church last December, they handed me a pamphlet with a bunch of questions and answers about their style of worship, and one of the questions they addressed was why they had so many icons. They said that they wished to worship God in every way, and that humans as physical beings were not only to worship God in our minds, but with our bodies and with everything that we created as well, hence the decorations in their church. The Catholic church has a similar stance, saying that we create art in order to venerate the things that we value. When I talk to people of the Reformed tradition, they believe in the same thing, and like to use the words "stewardship" and "cultural mandate," and they have formed a great deal of art to the glory of God.

That's what this film is about. It's trying to glorify God. It isn't asking for us to glorify Octavia Spencer, even though I'm sure some people walked out of the theatre idolizing her just as they idolize any actor who appears in a Christian movie, to which I say "Just because someone's famous and a Christian, that doesn't mean that they should be your role model." It isn't taking itself too seriously as a piece of art, as some films do, such as basically anything by Quentin Tarantino, who is constantly gratifying himself with his writing and directing style. The movie was trying to reach out to people who might have questions about their faith and answer them, and that's noble. I don't see too many people bowing down and worshiping the image of God seen onscreen, not in the same way as they bowed down to idols in the Old Testament, because that's not the spirit in which this film was created. It wasn't created to be a monument of religion to be adored.

If there is an issue with idolatry, it isn't the film's fault, but our own. We as Christians sometimes have a tendency to idolize the "goodness" of our sub-culture. We idolize our name-brand. Instead of making our only idol God's love for us, we put our ultimate sense of worth on "being Christian." That's something we should be weary of. You see this problem in the Jewish community. Only about 10% of Jews in America are Orthodox, seeing themselves as in a covenant with God and following the commands of the Torah. The rest are merely people born into Judaism, who like identifying with the Jewish culture, but don't live an actual covenant relationship with God. They do many Jewish things and take pride in the tropes that are associated with being Jewish, which is the same thing as when we Christians take pride in our art, and our churches, and our charities.

Here are some other thoughts that I have on idolatry: some people who look at Exodus 20:4 and take the literal interpretation that we should never make visual representations of anything, especially God, still think that its okay to write music about God. Isn't writing music sort of like creating an image, just for the sense of hearing? If a composer writes a piece of music designed to express the character of God, that's painting a portrait. Johann Sebastian Bach signed Soli Deo Gloria on every piece that he composed, "Glory to God Alone," and I always imagined that the piece "Toccata and Fugue in D Minor" was all about creating an image of the things in heaven above above and the earth beneath and the waters below, expressing through the mathematical harmony of his notes the essence of a perfect Creator Who knows all things and is in control of all history. Soli Deo Gloria. He created this purely for the glory of God, and so God finds this sacrifice of praise acceptable, just as He was pleased by Abel's sacrifice.

Sometimes I am more like Cain. I make offerings that seem like sacrifices, but they are for my own glory. That's what I struggle with sometimes when I put so much time and effort into a piece of art, because I begin to idolize the art instead of the Person that the art is dedicated to. That sacrifice becomes its own idol. Also, I'm guilty of treating the music of Beethoven and Bach like idols. Even though they are clearly inspired by God, and are of God, and point to God, I at times act like a wine-sipping cultural snob who's proud of himself for his pristine tastes in art. At that point, I begin idolizing the image of this music in the same way that people in the Old Testament would idolize images.

Every time we create art, we're depicting God in some way, whether we're creating a visual of how we'd imagine he'd look like in a vision, or in more subtle ways, because essentially all art is making a statement of the character of God. From my earliest days of writing, I understood that God was a major character in my stories because I was highly conscious that whatever happened in my stories could only occur if God willed for it to happen. That made me feel odd at first, and it still sort of does, because as a writer I was aware that everything I described in my stories made assumptions about God. I also felt weird that I was writing fiction, which involved me creating a world full of things that never happened in real life, the real life that God created and therefore intended. In writing fiction, I was writing a world that God had not intended. God reveals Himself and His character through history, and to write about something that never occurred in history is, in a sense, writing about a world with a God who revealed Himself in a different way than He has chosen to reveal Himself, and thus has a different character, and thus is a different God, and one can then claim that fiction is a false god. If literalists wish to take their interpretation of the first commandment to its logical extremes, they're realize that all fiction, all poetry, and all music is blasphemous.

Yet Jesus spoke in parables. He revealed Himself through His incarnation, but also through small bits of fiction. Perhaps one could say that the fiction given to us directly from God can count as valid historic revelation, but I'd argue that we have Jesus' Spirit in us, and therefore have the liberty to tell stories just as He did. If we are under the Law, then instead of learning to speak a living language, we'd just learn to recite quotes from the Bible all day long, Bible quotes would be the only things worth saying. All other possible normal, everyday phrases, such as "I would like pancakes for breakfast," would be sacrilegious, because we'd be taking language into our own hands and saying things that weren't dictated to us through God's historic revelation. True faith in the Law leaves no room for creativity, no room for progress, and no room for individuality. When we are in the Spirit, we don't have to constantly second-guess ourselves, and we can be free to be who we are. We are free to find new ways of revealing the character of God in new ways that have never been done before, and we know that our sacrifices to Him have His blessing, because though these are not revelations of the Law, these are still revelations of the Spirit.

When Jesus spoke in parables, He compared God to a woman who lost a coin and threw a party when She found it. He compared God to a father who rejoiced when He reunited with His prodigal son. We have the freedom to tell similar stories, because we have been moved and transformed from the inside so that we are now the Body of Christ. God lets us find truth from one another as we tell stories about Him, because truth can be found in His church. That's one of the ways in which I interpret Matthew 18:18, when Jesus says "Truly I tell you, whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven." God has revealed Himself by speaking from a flaming bush and through His incarnate Son, but He doesn't stop there. He continues to reveal Himself through His church — through her sermons, through her worship, through her stories, through her art, through her music, through her lives.

The Shack strikes me as a retelling of the parable of the woman who lost her coin, as if the author, William Paul Young, were trying to tell it in his own words. That's not blasphemy, and that's not idolatry. That is teaching, as Christ taught, and it has His blessing, because the Spirit is talking through the author. Even though it doesn't match the exact wording that Jesus used, and in a legalistic sense has fallen short of the glory of God, because no Christian artwork is technically perfect, the story still comes from the Spirit of God. It saddens me when Christians so harshly judge other Christians and are slow to trust or forgive each other. People have been telling others not to see this film, because they are paranoid and afraid, but fear does not come from the Spirit. A Christian is capable of watching an imperfectly written screenplay and still getting the Spirit from it. We sometimes become frightened and start judging God when He allows someone freedom to walk as they please in the Spirit, but we must learn to let that sense of judgment go. Yes, we should always have wise discernment, but we're also called to be united. What I have seen is division between Christians because of this film, and that isn't something that we can be content with. If we can't all agree on finer theological points, that's okay, but we must remember that the Spirit that unites us is stronger than the spirit that divides us.

Soli Deo Gloria,

John

Allow me to explain idolatry. Idolatry is, first and foremost, valuing anything more than God. God must be the source of all value and the central focus of our lives, our reason for living. That's how most adults understand idolatry today, and just about any church that I go to will make a point of mentioning that it's even possible to idolize our spouses and children. We can idolize other things. Some of us put our ultimate self-worth in our jobs, and that's idolatry. I see many humanistic people idolize the arts; just listen to Viola Davis's acceptance speech at the Oscars, or what Meryl Streep said at the Golden Globes. When you tune into those award ceremonies, you're basically watching a bunch of wealthy people congratulating themselves on the art that they created, and defining themselves by their artistic achievements. It's completely disconnected from the real world that matters.

This is where I have to confess something, actually. I worship art. Specifically, good art. Truly, I do. I am idolatrous. As an artist, I am particularly vulnerable to this, because I see art in a different way than others. I become proud and attached to my own art when I've completed it. I adore it. What can I say? I put hard work into it, so it's hard not to value it! When I see good art, I tend to take it very seriously, more seriously than I should. Perhaps I even become jealous of the artist who created it, because I wish I could have accomplished what they have accomplished. I'm jealous of Steven Spielberg, because he gets to make films with John Williams scores. I'm jealous of George Lucas and J.R.R. Tolkien, because they created the two greatest works of fantasy in modern art that I'm always afraid that I will never live up to. Because I idolize these images, I break another commandment, because I begin coveting my neighbor's wife.

Furthermore, I want to write my books series. I put my self-worth in self-expression. This self-expression in many ways makes me vulnerable, which is a virtue, but I begin idolizing that virtue instead of putting my faith in God's love for me. I begin making the meaning of my life all about how perfect I can make my art, but that's not why I was created. I was created to be loved. Idolatry distracts me from that.

That is the most dangerous kind of idolatry, and that is the evil spirit that Exodus 20:4 ultimately wishes to protect us from. Boiling it down to this ridiculous formula of "All art depicting sacred things is bad" is oversimplifying the command, and missing the point. God commanded the Jews to make many beautiful things, including statues of cherubim. The trick here was that God didn't want the Jews to worship the art itself, but what it represented. We humans are visual creatures, and often do need physical prompts to remind us of the things that we value. When I went to a Greek Orthodox church last December, they handed me a pamphlet with a bunch of questions and answers about their style of worship, and one of the questions they addressed was why they had so many icons. They said that they wished to worship God in every way, and that humans as physical beings were not only to worship God in our minds, but with our bodies and with everything that we created as well, hence the decorations in their church. The Catholic church has a similar stance, saying that we create art in order to venerate the things that we value. When I talk to people of the Reformed tradition, they believe in the same thing, and like to use the words "stewardship" and "cultural mandate," and they have formed a great deal of art to the glory of God.

That's what this film is about. It's trying to glorify God. It isn't asking for us to glorify Octavia Spencer, even though I'm sure some people walked out of the theatre idolizing her just as they idolize any actor who appears in a Christian movie, to which I say "Just because someone's famous and a Christian, that doesn't mean that they should be your role model." It isn't taking itself too seriously as a piece of art, as some films do, such as basically anything by Quentin Tarantino, who is constantly gratifying himself with his writing and directing style. The movie was trying to reach out to people who might have questions about their faith and answer them, and that's noble. I don't see too many people bowing down and worshiping the image of God seen onscreen, not in the same way as they bowed down to idols in the Old Testament, because that's not the spirit in which this film was created. It wasn't created to be a monument of religion to be adored.

If there is an issue with idolatry, it isn't the film's fault, but our own. We as Christians sometimes have a tendency to idolize the "goodness" of our sub-culture. We idolize our name-brand. Instead of making our only idol God's love for us, we put our ultimate sense of worth on "being Christian." That's something we should be weary of. You see this problem in the Jewish community. Only about 10% of Jews in America are Orthodox, seeing themselves as in a covenant with God and following the commands of the Torah. The rest are merely people born into Judaism, who like identifying with the Jewish culture, but don't live an actual covenant relationship with God. They do many Jewish things and take pride in the tropes that are associated with being Jewish, which is the same thing as when we Christians take pride in our art, and our churches, and our charities.

Here are some other thoughts that I have on idolatry: some people who look at Exodus 20:4 and take the literal interpretation that we should never make visual representations of anything, especially God, still think that its okay to write music about God. Isn't writing music sort of like creating an image, just for the sense of hearing? If a composer writes a piece of music designed to express the character of God, that's painting a portrait. Johann Sebastian Bach signed Soli Deo Gloria on every piece that he composed, "Glory to God Alone," and I always imagined that the piece "Toccata and Fugue in D Minor" was all about creating an image of the things in heaven above above and the earth beneath and the waters below, expressing through the mathematical harmony of his notes the essence of a perfect Creator Who knows all things and is in control of all history. Soli Deo Gloria. He created this purely for the glory of God, and so God finds this sacrifice of praise acceptable, just as He was pleased by Abel's sacrifice.

Sometimes I am more like Cain. I make offerings that seem like sacrifices, but they are for my own glory. That's what I struggle with sometimes when I put so much time and effort into a piece of art, because I begin to idolize the art instead of the Person that the art is dedicated to. That sacrifice becomes its own idol. Also, I'm guilty of treating the music of Beethoven and Bach like idols. Even though they are clearly inspired by God, and are of God, and point to God, I at times act like a wine-sipping cultural snob who's proud of himself for his pristine tastes in art. At that point, I begin idolizing the image of this music in the same way that people in the Old Testament would idolize images.

Every time we create art, we're depicting God in some way, whether we're creating a visual of how we'd imagine he'd look like in a vision, or in more subtle ways, because essentially all art is making a statement of the character of God. From my earliest days of writing, I understood that God was a major character in my stories because I was highly conscious that whatever happened in my stories could only occur if God willed for it to happen. That made me feel odd at first, and it still sort of does, because as a writer I was aware that everything I described in my stories made assumptions about God. I also felt weird that I was writing fiction, which involved me creating a world full of things that never happened in real life, the real life that God created and therefore intended. In writing fiction, I was writing a world that God had not intended. God reveals Himself and His character through history, and to write about something that never occurred in history is, in a sense, writing about a world with a God who revealed Himself in a different way than He has chosen to reveal Himself, and thus has a different character, and thus is a different God, and one can then claim that fiction is a false god. If literalists wish to take their interpretation of the first commandment to its logical extremes, they're realize that all fiction, all poetry, and all music is blasphemous.

Yet Jesus spoke in parables. He revealed Himself through His incarnation, but also through small bits of fiction. Perhaps one could say that the fiction given to us directly from God can count as valid historic revelation, but I'd argue that we have Jesus' Spirit in us, and therefore have the liberty to tell stories just as He did. If we are under the Law, then instead of learning to speak a living language, we'd just learn to recite quotes from the Bible all day long, Bible quotes would be the only things worth saying. All other possible normal, everyday phrases, such as "I would like pancakes for breakfast," would be sacrilegious, because we'd be taking language into our own hands and saying things that weren't dictated to us through God's historic revelation. True faith in the Law leaves no room for creativity, no room for progress, and no room for individuality. When we are in the Spirit, we don't have to constantly second-guess ourselves, and we can be free to be who we are. We are free to find new ways of revealing the character of God in new ways that have never been done before, and we know that our sacrifices to Him have His blessing, because though these are not revelations of the Law, these are still revelations of the Spirit.

When Jesus spoke in parables, He compared God to a woman who lost a coin and threw a party when She found it. He compared God to a father who rejoiced when He reunited with His prodigal son. We have the freedom to tell similar stories, because we have been moved and transformed from the inside so that we are now the Body of Christ. God lets us find truth from one another as we tell stories about Him, because truth can be found in His church. That's one of the ways in which I interpret Matthew 18:18, when Jesus says "Truly I tell you, whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven." God has revealed Himself by speaking from a flaming bush and through His incarnate Son, but He doesn't stop there. He continues to reveal Himself through His church — through her sermons, through her worship, through her stories, through her art, through her music, through her lives.

The Shack strikes me as a retelling of the parable of the woman who lost her coin, as if the author, William Paul Young, were trying to tell it in his own words. That's not blasphemy, and that's not idolatry. That is teaching, as Christ taught, and it has His blessing, because the Spirit is talking through the author. Even though it doesn't match the exact wording that Jesus used, and in a legalistic sense has fallen short of the glory of God, because no Christian artwork is technically perfect, the story still comes from the Spirit of God. It saddens me when Christians so harshly judge other Christians and are slow to trust or forgive each other. People have been telling others not to see this film, because they are paranoid and afraid, but fear does not come from the Spirit. A Christian is capable of watching an imperfectly written screenplay and still getting the Spirit from it. We sometimes become frightened and start judging God when He allows someone freedom to walk as they please in the Spirit, but we must learn to let that sense of judgment go. Yes, we should always have wise discernment, but we're also called to be united. What I have seen is division between Christians because of this film, and that isn't something that we can be content with. If we can't all agree on finer theological points, that's okay, but we must remember that the Spirit that unites us is stronger than the spirit that divides us.

Soli Deo Gloria,

John

No comments:

Post a Comment